Since I first started getting the idea in my head to create a fantastical world and stories of adventures that I could share with a wider audience beyond the pen and paper RPGs that I was running, the one biggest thing that I have been struggling with the most for the entire 13 years was to figure out what kind of people the protagonists would be, and what kind of things they would be doing that keeps pulling them into the kinds of adventures that are meaningful to me. Even back then I had already gotten bored with the fantasy of being a one man army who ends up with a kill count of 300 enemy soldiers and 400 monsters, who is doing all of this to become a hero and gain riches. When put like that, and I believe it is accurate for most adventure fiction and especially dungeon crawling fantasy, it actually sounds really fucked up. Could you imagine being a 20-something who has stabbed hundreds of people dead or incinerated them in magical fire, and who has been impaled by spears dozens of times and still remain a remotely sane person?

I think violence is an incredibly compelling topic. I believe it’s an integral part of human nature and something that can frighten, disgust, excite, and attract us at the same time. And how we can make sense of these conflicting instincts that are contradicting all the values we believe in and deal with them is an endlessly fascinating topic to explore. But the vast majority of adventure fiction does not explore any of this at all and simply revels in the spectacle of carnage, or actively glamorizes and revels in it. Which is something that has bothered me with much of the fiction I’ve read, watched, and played, and I find more than a bit disturbing. I always knew that the generic adventure plots of “kill the enemies, take the treasures, save the day” wouldn’t do it for me. But how else do you get a character who ends up climbing down into dangerous caves and wrecks, faces fantastic monsters, evades deadly traps, and discovers magical wonders, and then just keeps doing that again and again?

The concept I had for Iridium Moons for the last half year or so was that of playing as a salvager. Someone who goes to ruined factories, abandoned mines, or wrecked ships to find valuable spare parts that haven’t been manufactured for generations but are now incredibly valuable for people desperate to keep ancient and irreplaceable machines running. This would support gameplay in which you mostly explore the wilderness, navigate through ruins, fix broken doors and machinery to get access to other areas, and mostly try to avoid enemies and escape with your life. Which I think is a very solid idea, that should work just as well of having the game protagonist be a thief or a lunatic who thinks killing monsters is a good way to make a living. You can absolutely make an entire game about that. But it is also rather limiting in what kind of stories you can tell with it in a game that is not only an endless gameplay loop like a Rogue-like or Survival/Crafting game, but also explores the characters and society of its world.

I have considered scrapping this idea entirely and instead coming up with a completely new concept to turn the world of Iridium Moons into a game for the last weeks. But I think all the gameplay ideas I had planned could actually still make a fantastic game by simply expanding the archetype of who the players’ characters are and what they do? Instead of being specifically salvagers who make a living following leads to find old machine parts, I am now envisioning a broader concept of playing as a more generic “scout”.

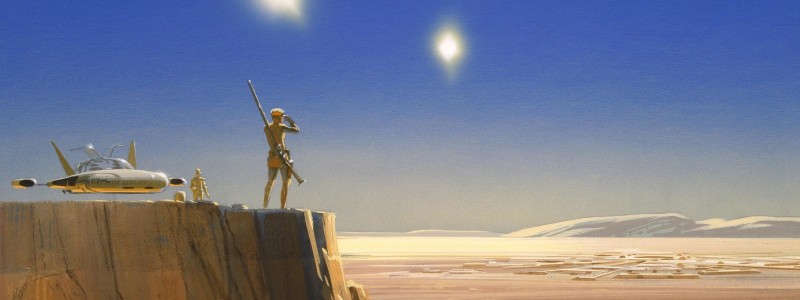

The idea I have in mind for the game is not so much an explorer, surveyor, and prospector who is the first to set foot on a new planet and discover if it has any value for companies or colonists, as the term is often used in pen and paper Space RPGs. But rather someone who has the skills and the equipment to find things that have been lost in the wilderness. In many popular space adventure settings, this probably wouldn’t feel like an established or very adventurous profession, as the established technologies for reaching locations and detecting things are often highly effective and ubiquitous, making the part about finding things something that is largely glossed over as it is assumed to be not much of a challenge to spend time on. But the worldbuilding for Iridium Moons that I’ve already done over the last year may actually make it uniquely well suited as a setting for such adventures and gameplay. Detection technology is no better than what we have access to today, and the planets of the Galia Cluster have very small populations that are highly decentralized and dispersed. Many smaller communities don’t have the means to search huge areas of wilderness and won’t be getting any support from the big cities that do. And with the fierce rivalry and constant infighting among the Oligarchs, and the ruthless power struggles among their underlings, there are plenty of reasons not to make use of the official search teams.

I am a huge fan of wandering around in Morrowind, Skyrim, Stalker, and Metro Exodus, exploring the environments, looking for paths to get past obstacles, and searching for hidden things. But once I find things, I am generally really not a fan of fighting through dozens of enemies that occupy a ruin, or constantly managing my inventory to figure out what things to take back with me and what to leave behind. And especially not collecting piles of dozens of different resources, which I then can turn into some junk, which unlocks other junk on the tech tree for which I have to go back and collect more resources to build. Which is why survival crafting games generally don’t work for me. I would much rather have a game, and make a game, which is just about the wandering around and exploring part, but with most of the combat gameplay instead being interesting stealth gameplay, and without having to haul around a lot of stuff that requires constant inventory management. Playing a character who gets paid to find things that are in an unknown location, instead of a character who’s objective is to collect things, could be a concept that could make this work as engaging gameplay.

Working as an independent scout provides plenty of different types jobs that players could take on:

- Find missing people.

- Find escaped fugitives.

- Find bandit hideouts.

- Find missing ships.

- Recover lost cargo.

- Retrieve someone else’s cargo.

- Deliver secret cargo.

- Locate abandoned equipment for salvage.

- Investigate unknown signals or anomalies.

I see a lot of potential in these for the kinds of stories that I am personally interested in, involving the kind of characters that I find compelling. And make for wonderful reasons to travel through vast landscapes in an airship, on a hoverbike, and on foot as the search is closing in on the target, which lets players take in the sights and sounds without being hurried along by action while still investigating the world for clues and planning out their next steps as they are moving, making it more than just idle time that makes you consider using fast travel.

I am feeling quite good about this, and more optimistic than all the other ideas I’ve been exploring before.