At this stage of the development, the humanoid species that inhabit the Iridium Moons setting are still not completely locked in and I am still occasionally making some changes to the full lineup. But that has been limited to the smaller players on the interstellar stage, and the main species that make up the core of big influential power groups and the majority of the populations on most planets have been very well set for many months now. The peoples covered in this post will almost certainly remain largely as they are now in the final version of the setting, and by having these five introduced for now there should be enough established context to let me meaningfully write about all kinds of other aspects of the setting I already have to share.

While the theory and technological requirements behind the construction of hyperspace drives is comparatively straightforward and has been developed many times independently, the science of being able to actually navigate a ship moving through hyperspace is widely considered to be the greatest challenge is physics and known to have been discovered only twice in the history of the galaxy. Even on planets that had developed spaceflight several thousands of years earlier, the ability to travel to other star systems only became available to their people once they had been visited by ships from other worlds that shared the secrets of hyperspace navigation with them. In the centuries since the Damalin discovered hyperspace travel, the homeworlds of some two dozen advanced civilizations have been connected to the hyperspace route network established by them. About half of which have since then developed interstellar industries and established outposts and colonies in other systems and are regularly encountered in spaceports across Known Space. Of these peoples, five make up a significant majority of travelers, workers, and settlers outside of the home systems and control most of the interstellar mining industry and starship manufacturing.

Enkai

Of all the peoples working and living in interstellar space, the Enkai are the most numerous. They were one of the first civilizations discovered by the Damalin after their rediscovery of hyperspace travel and since then have established dozens of colonies, many of which have by now grown to populations in the tens of millions.

Of all the peoples working and living in interstellar space, the Enkai are the most numerous. They were one of the first civilizations discovered by the Damalin after their rediscovery of hyperspace travel and since then have established dozens of colonies, many of which have by now grown to populations in the tens of millions.

Enkai are of medium stature compared to other peoples and typically stand out even from a distance by their striking orange-red skin. Their homeworld is dominated by a comparatively drier climate than the planets on which most other species evolved, and while they are most comfortable in moderately warm savanna environments, this makes them one of the most tolerant peoples for the harsh desert environments that are most common on planets with breathable air. While Enkai are somewhat of a rare sight in colonies with wet and humid climates, this environmental adaptation has made them become the most widely spread out and numerous people of interstellar space.

Even compared to the other civilizations of Known Space, the Enkai culture is highly fragmented and the large population of their homeworld divided into over a hundred fully sovereign nations and no single representative organization in interstellar affairs. While now relatively rare, minor wars on the Enkai homeworld still happen every other decade, typically unnoticed by the rest of the galaxy. Enkai living in interstellar space typically identify strongly with their own home planet but generally lack much of a shared identity as a species as is common with most of the other peoples. In complex conflicts, the species of other groups generally have no meaningful impact on which sides they pick.

Damalin

Unlike most of the species of Known Space, the Damalin already traveled between the stars over 2000 years ago. Their homeworld used to be a minor client state of a vastly larger interstellar civilization, on which their ancient spacefarers relied entirely for ships and navigational charts. When this older civilization fractured and showed signs of collapse, the Damalin homeworld was one of the first that became separated from the hyperspace route network and without regularly updated navigational data, their few hyperspace jump capable ships became stranded in the system. It took many centuries for the Damalin to economically recover from the loss of interstellar trade and over a thousand years before they managed to independently develop the technologies to create new hyperspace chart. By that time the nearby colony worlds that the Damalin used to have direct contact with had long been abandoned and they have never been able to discover what eventually happened to the older civilization. The Damalin system for creating navigational charts and hyperspace routes became the basis for the entire currently existing network of routes that make up Known Space.

The Damalin are an amphibious species of slender humanoids who tend to be on the taller side for the peoples of Known Space but rarely grow over 2 meters tall. They can breath both air and water indefinitely but quickly develop skin irritation when out of water for more than a day or two. Long showers will do in an emergency, but all Damalin ships and homes have often several bathtubs used for naps when larger fully submerged areas are not possible. Even though they are not a particularly numerous people, Damalin have been establishing colonies in other systems for such a long time that they are common sights nearly everywhere in space, and Damalin patricians own many of the oldest and largest interstellar companies.

Netik

The Netik civilization is incredibly old, being believed to first developed agriculture and build the first cities on their homeworld nearly 60,000 years ago. However, the Netik who today inhabit the worlds of Known Space are all descendants of ancient colony worlds established long ago in the age of the previous interstellar civilization that first brought hyperspace travel to the Damalin as well. When the ancient civilization collapsed, the Netik had already spread across many worlds, which eventually became separated from the hyperspace route network and remained isolated for well over a thousand years. When the Damalin rediscovered interstellar space travel, nearby Netik colonies were the first planets they visited in their explorations. Many of which had gone extinct over the centuries, but a number of them that had been established on planets with particularly favorable environments had grown to populations in the hundreds of millions in the meantime. Once they regained the ability to travel between the stars, these Netik colonies quickly began looking for other surviving colonies, but even in nearly 500 years of searching, they have never been able to rediscover their original homeworld. As a people without a homeworld, the Netik are far less numerous than any other. But with the populations of the other peoples living almost entirely on their respective homeworlds, the Netik are actually make up a large fraction of the population of interstellar space, being nearly as common as Enkai and Damalin.

Even though the physical appearance of Netik is regarded as highly alien to most other peoples of Known Space, they actually have a well deserved reputation of being very easy to get along and having a highly developed ability to judge emotions and finding the right way to talk with people that they react well to. Netik companies are heavily involved in the space mining industry and the construction of the largest superfreighters used for ore hauling.

Chosa

The Chosa are tall humanoids with tough green-gray hides and sharp teeth that give them a reptilian appearance, but otherwise very similar to Enkai in their overall body structure and stature. They are among the physically strongest of the species traveling interstellar space and fight fiercely and with little hesitation. Prejudices are widely spread among the other species of Chosa being violent brutes, but their homeworld actually ranks among the most technologically advanced planets in Known Space. Their ships tends towards blocky and practical designs typically regarded as looking blunt with little thought for decorations, but compare well in their capabilities to all but the most sophisticated Damalin and Netik ships.

Chosa encountered in space are often mercenaries, an occupation that their physical toughness and familiarity with advanced space technologies makes them well suited for. Chosa culture as a whole is not overly militaristic though, and their prominent presence in the mercenary business comes more from them being very well suited for the demands of that line of work. There are typically not a lot of opportunities for Chosa engineers or pilots outside of Chosa systems, but they are on average not far behind in their skills than the Damalin, Netik, and Enkai who dominate the profession.

Tubaki

The Tubaki are one of several peoples whose presence in space is greatly dependent on technologies and infrastructures of other species. There is only a small number of Tubaki shipyards and most of them are primarily specialized on converting old purchased ships from other manufacturers to provide greater comfort to Tubaki crews. Those shipyards that do build their own ships still rely on imported hyperspace drives and gravity generators from other more established companies. Despite Tubaki worlds being generally seen as more low tech planets, Tubaki have been traveling through space for centuries and founded several dozen of colonies in other sectors. Even though most of them are of no interest or relevance for major interstellar companies.

Tubaki are humanoids quite similar in size and proportions to Enkai, which is generally attributed to the very similar gravity and climatic conditions on the Tubaki and Enkai homeworlds producing a similar optimal body shape for upright walking humanoids. On average, Tubaki tend to be slightly taller and more muscular, but mostly stand apart due to their sand to brown colored fur and thick manes. Tubaki found outside their own system are usually employed as manual labor, primarily in mining and agriculture and also various low-level mechanic jobs. Tubaki colonies are usually too small to have advanced engineering and science schools and those individuals with advanced degrees typically find their calling in contributing to the development of their planets rather than seeking their luck among the stars.

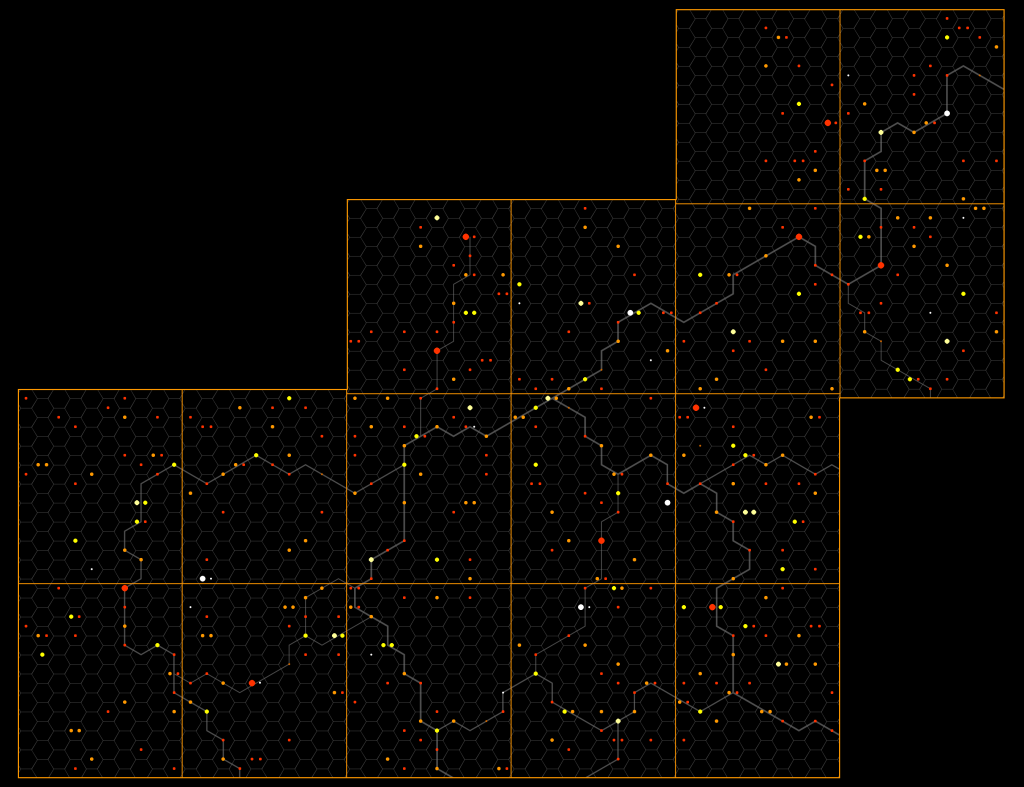

The New Frontier Survey was one of the largest astrometric survey projects ever undertaken in the history of Known Space and has not been surpassed in the following more than 300 years. A consortium of many of the largest mining companies at the time comissioned the surveying and calculation of hyperspace routs for 16 new sectors, increasing the mapped area of the galaxy by over 5%. Great hopes had been placed on the discovery of significant easy to access resource deposits, and while initial exploration missions to the most promising systems turned out quite promising, the overall commercial success of the project has become widely regarded as somewhat disappointing by the space mining industry.

The New Frontier Survey was one of the largest astrometric survey projects ever undertaken in the history of Known Space and has not been surpassed in the following more than 300 years. A consortium of many of the largest mining companies at the time comissioned the surveying and calculation of hyperspace routs for 16 new sectors, increasing the mapped area of the galaxy by over 5%. Great hopes had been placed on the discovery of significant easy to access resource deposits, and while initial exploration missions to the most promising systems turned out quite promising, the overall commercial success of the project has become widely regarded as somewhat disappointing by the space mining industry. Of all the peoples working and living in interstellar space, the Enkai are the most numerous. They were one of the first civilizations discovered by the Damalin after their rediscovery of hyperspace travel and since then have established dozens of colonies, many of which have by now grown to populations in the tens of millions.

Of all the peoples working and living in interstellar space, the Enkai are the most numerous. They were one of the first civilizations discovered by the Damalin after their rediscovery of hyperspace travel and since then have established dozens of colonies, many of which have by now grown to populations in the tens of millions.